It has been over 60 years since Osamu Shimomura et al. discovered Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)1. Since then, the color palette for fluorescent proteins has been extended to span blue through to far red, and even includes proteins that are capable of exhibiting photochromism. While it would be impossible to cover every fluorescent protein here, this article looks at some of the options available to researchers.

The Discovery of GFP

Before his name became irrevocably linked with the discovery of GFP, Osamu Shimomura was involved in studying the bioluminescence of Cypridina hilgendorfii, also known as the sea firefly. However, his success in purifying and crystallizing Cypridina luciferin, which had never been done before, soon led to a position at Princeton University, where he was invited to investigate a similar phenomenon in Aequorea jellyfish.

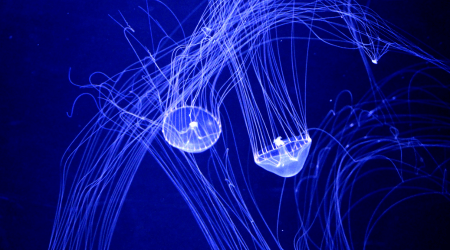

Aequorea Jellyfish

After quickly finding that established methods for extracting luciferin did not work for Aequorea, Shimomura developed a novel technique using the calcium chelator EDTA, which was applied for extracting the luminescent substance (aequorin) from around 10,000 jellyfish. During the purification process, a protein exhibiting bright green fluorescence was found in trace amounts. This was accumulated gradually over the next decade, while efforts focused on understanding aequorin luminescence.

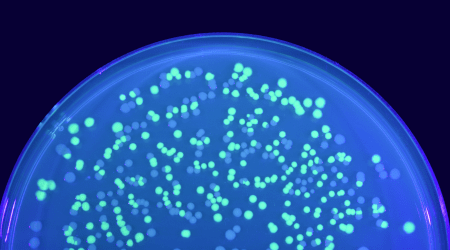

In 1971, the green protein was named GFP by Morin and Hastings, who suggested that the observed fluorescence was due to a Förster-type energy transfer from aequorin.2 GFP was subsequently crystallized in 1974 and the chromophore structure elucidated in 1979, but it was not until 1992 that the GFP gene was sequenced to enable its use as a recombinant protein tag3,4,5. Just two years later, Chalfie et al. expressed GFP in E. coli and C. elegans, paving the way for future experiments in mammalian cells6.

GFP Engineering

In 1995, the introduction of a single point mutation (S65T) improved wild-type GFP by increasing the brightness and accelerating the maturation time, allowing for fluorescence to be detected sooner following cell transfection7. Then, in 1996, a second point mutation (F64L) was added to yield enhanced GFP (EGFP), which is one of the brightest and most photostable Aequorea-based fluorescent proteins8. Continued engineering has produced further GFP variants, including other green emitters (e.g., Emerald GFP, Superfolder GFP, and T-Sapphire), as well as blue (e.g., BFP, EBFP, and Azurite), cyan (e.g., Cerulean, mTurquoise, and ECFP), and yellow fluorescent proteins (e.g., EYFP, Citrine, and Topaz).

E. coli cells expressing GFP

Fluorescent Proteins From Other Species

Compared with GFP and its derivatives, red fluorescent proteins (RFPs) offer several advantages. First, they enable deeper imaging into biological tissue, because the signal they produce is less affected by yellow-green cellular autofluorescence. RFPs also allow for imaging over a longer timeframe, since living cells and tissues can better tolerate illumination by the longer excitation wavelengths. These desirable properties of RFPs have driven efforts to find novel fluorescent proteins in other species than Aequorea.

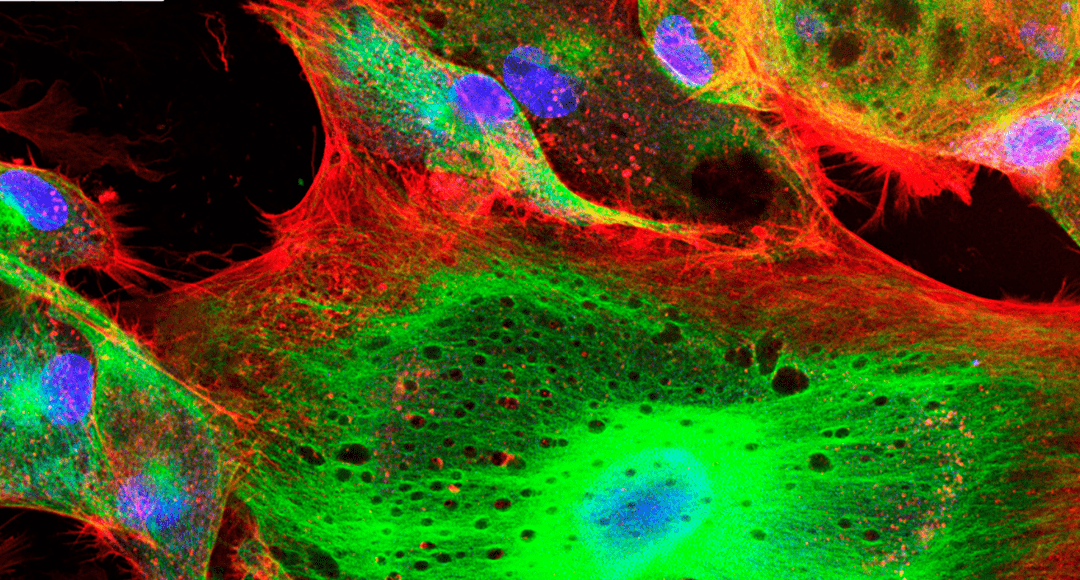

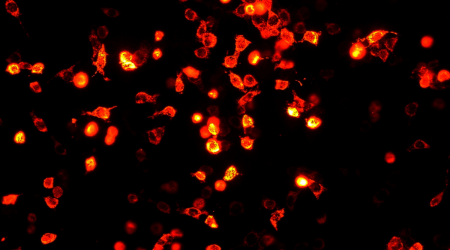

Cells expressing RFP

Despite being a little out of date, this 2017 publication provides a helpful pictorial representation of fluorescent proteins introduced since 19929. Well-known examples include DsRed, which is derived from the coral Discosoma and represents the first RFP to be discovered; mCherry, a pH resistant DsRed derivative; and allophycocyanin (APC), a highly fluorescent hexameric protein found in cyanobacteria.

Functionality by Design

Besides structure-based mutagenesis (as used to generate EGFP), new fluorescent proteins have been developed through directed evolution, whereby gene diversification is followed by the selection of clones with specific properties. For example, this approach enabled the development of smURFP, a smaller, more stable derivative of APC with an exceptionally large extinction coefficient (ε = 180,000 M−1cm−1) and similar fluorescent brightness to EGFP10.

Other engineered functionalities include photoactivation, photoswitching, and photosensitization. For example, the photoactivatable protein PA-GFP is devoid of fluorescence until exposed to 488 nm light, giving it utility for tracking intracellular protein dynamics11. And the photoswitchable protein PS-CFP converts from cyan to green in response to 405 nm irradiation, making it useful for fluorescence resonance energy transfer applications12. In terms of photosensitization, both KillerRed and its monomeric variant (SuperNova) generate reactive oxygen species upon irradiation with green light to effect cell killing13,14.

Applications of Fluorescent Proteins

In addition to the applications just described, fluorescent proteins have many other important uses. They can serve as reporter genes to study gene regulation or evaluate transfection efficiency, depending on the expression construct that is used, as well as represent useful labels for flow cytometry and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) experiments. Fluorescent proteins can also be split into fragments that spontaneously reassemble into a functional biomolecule during bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), a technique which is used for exploring protein-protein interactions15. Moreover, GFP can be bound by anti-GFP antibodies during applications such as protein purification and microscopy-based imaging.

Supporting Your Research

Whether you’re using fluorescent proteins or synthetic dyes, FluoroFinder can help you find the right reagents for your project. Leverage our Antibody Search tool to identify antibodies for your chosen target, species, and application. Then use our Spectra Viewer to identify fluorophores matching your instrument’s laser and filter configurations.

References

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13911999/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4397528/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4151620/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0014579379808182

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1347277/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8303295/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7854443/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8707053/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27814948/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27479328/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12228718/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15502815/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16369538/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24043132/

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ja994421w